Wat een lef hè; het is 1965 en de Sint Agnes parochie van de in februari 1945 zwaar gebombardeerde wijk in Kreuzberg, geeft opdracht een nieuw godshuis te bouwen. De dan zeer succesvolle architect Werner Düttmann ontwerpt de kerk met klokkentoren, het parochiehuis, kinderopvang en een woning voor de pastoor en koster. Materiaal: beton van vermalen steen afkomstig van de dan nog altijd aanwezige ‘Trümmerhaufen’, de restanten van de platgegooide woningen in dat deel van de stad.

Het werd een streng geometrische constructie, ‘mit wortkarge Wände’, met zwijgzame (woordloze, stille?) wanden (muren?).

Het gebruik van onbewerkt beton, ‘béton brut’ genereerde de naam van een architectonische stroming, het brutalisme, waarvan Düttmann in Duitsland een belangrijke representant is.

In 2011 pacht galeriehouder Johann König het hele complex voor de duur van 99 jaar, liet het renoveren en slim aanpassen tot een multifunctionele ruimte door Brandlhuber architects.

https://www.koeniggalerie.com/

https://bplus.xyz/

What guts!; it is 1965 and the Saint Agnes parish of the in February 1945 heavily bombed neighborhood in Kreuzberg, orders a new almshouse to be built. The then very successful architect Werner Düttmann designed the church with a bell tower, the parish house, childcare, and a house for the priest and sexton. Material: concrete of crushed stone from the then still present ‘Trümmerhaufen’, the remains of the destroyed houses in that part of the city.

It was a strictly geometric construction, ‘mit wortkarge Wände‘, with taciturn (wordless, silent?) walls

The use of raw concrete, ‘béton brut’, generated the name of an architectural movement, brutalism, of which Düttmann is an important representative in Germany.

In 2011, gallery owner Johann König leased the entire complex for 99 years, had it renovated and cleverly adapted into a multifunctional space by Brandlhuber architects.

Op de radio hoorde ik een interessant programma over de strijd die er in de Koude Oorlog óók woedde op het gebied van bouwen. Prestigieuze projecten aan beide zijden van de muur, waarin men elkaar probeerde te overtreffen. De Karl Marx Allee in het Oosten tegenover het

sociale woningbouw project Hansaviertel in het Westen, waar Niemeyer, Alvar Aalto en Walter Gropius konden bouwen. Düttmann was daarin als bouwmeester en architect een leidend figuur.

En aan de andere kant van de muur was dat Hermann Henselmann, noodgedwongen enige tijd werkzaam in de neo classicistische, stalinist pompeuze stijl waarin de heren in Moscou het liefst gebouwd zagen worden. Later was hij veel meer een modernist, met Bauhaus wortels.

Opvallend is dat na de val van de muur, de oude, in verval geraakte 19de eeuwse wijken in het Oosten zeer in trek waren, bij de West Duitsers, terwijl het modernisme huizen en flats had opgeleverd waarin men aanvankelijk niet meer wilde wonen. Dat is langzaam aan het keren.

On the radio, I heard an interesting program about the battle that was also fierce in the field of building and urban planning during the Cold War. Prestigious projects on both sides of the wall, in which they tried to outdo each other. The Karl Marx Allee in the East opposite the social housing project Hansaviertel in the West, where Niemeyer, Alvar Aalto, and Walter Gropius could build. Düttmann was a leading figure in this as a master builder and architect.

And on the other side of the wall, it was Hermann Henselmann, who was forced to work for some time in the neoclassical, Stalinist pompous style in which the gentlemen in Moscow preferred to see construction. Later he was much more of a modernist, with Bauhaus roots.

It is funny that after the fall of the wall, the old, dilapidated 19th-century neighborhoods in the East were very popular with the West Germans, while modernism had resulted in houses and flats in which people initially no longer wanted to live. That is slowly changing now.

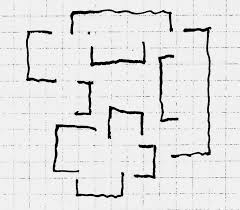

One of the first sketches for Düttmann’s new Brücke Museum.

Düttmann bouwde in dezelfde tijd het Brückemuseum in de landelijke omgeving van Dahlem, dat ter gelegenheid van zijn honderdste geboortedag een tentoonstelling organiseert waarbij het museum -zo begrijp ik, zien kunnen we het nog niet- leeggeruimd is om de schoonheid van zijn architectuur te tonen.

Zoals Ann Goldstein bij de heropening van het Stedelijk Museum deed, wat me toen zeer stoorde omdat we er eindelijk weer toegang toe hadden, er zoveel moois in het depot stond en de zalen er juist niet beter op geworden waren.

Inspelend op de corona-beperkingen heeft het museum een drietal wandelingen georganiseerd langs de 28 bouwwerken van Düttmann. Met opvallende informatieborden, QR codes en een hartstikke goeie website.

At the same time, Düttmann built the Brückemuseum in the woody area of Dahlem, which is organizing an exhibition on the occasion of his hundredth birthday in which the museum – I understand, we cannot see it yet – has been cleared out to show the beauty of its architecture.

As Ann Goldstein did at the reopening of the Stedelijk Museum, which really bothered me at the time because we finally had access to it again, and so much in stock, and the rooms had not improved.

In response to the corona restrictions, the museum has organized three walks along the 28 buildings of Düttmann. With striking information boards, QR codes and a really good website.

And what did Johann König put in front of the entrance to that austere building, his gallery?

This sculpture of Erwin Wurm!